Chinese Alligator – Species on the Brink

“According to a survey in 1998, only 120 wild Yangtze crocodiles [are] left. In the past, the number should be between 10,000 and one million,” continued Xie Yun, during an interview at the Anhui Research Center of Alligator Reproduction (ARCAR).

Xie Yan and I coincidentally met this week when we both visited ARCAR. ARCAR is situated in the city of Xuancheng, a few hours by train west of Shanghai. Established in the early 1980s, the center comprises of a series of ponds housing some 10,000 captive bred Chinese alligators. The aim of my visit there this week was to investigate the impact of wetland disappearance on the Chinese alligator and to get an idea of what is being done to protect these animals.

First, I wanted to identify the root causes for the species disappearance. As Xie Yan explained to me, disappearance began over fifty years ago.

“The main reason was the reclamation of lakes during the 1950s and 1960s. Farmers considered alligators as vermin, which ate their fish and other aquatic animals. With the increase of population and the area of farmland, the alligators’ habitat became smaller. People didn’t like to have dangerous species around, so the number of alligators dropped dramatically in 1950s and 1960s.”

During the 1970s and 1980s, numbers continued to drop as the Chinese alligators’ habitats shrank even further. “During the 1970s, the number of alligators dropped sharply. The main reason was people killing them for meat, for fear, and as vermin. Also, the overuse of fertilizer affected their egg laying and breeding.”

The decline reached its peak at the end of the 1990s when, in 1998, the biggest habitat for Yangtze crocodile was one small pond surrounded by farmland. There were 11 crocodiles in the pond. This rapid decline in the 1980s and 1990s spurred the government into action and along with the ARCAR, a mass breeding program was launched.

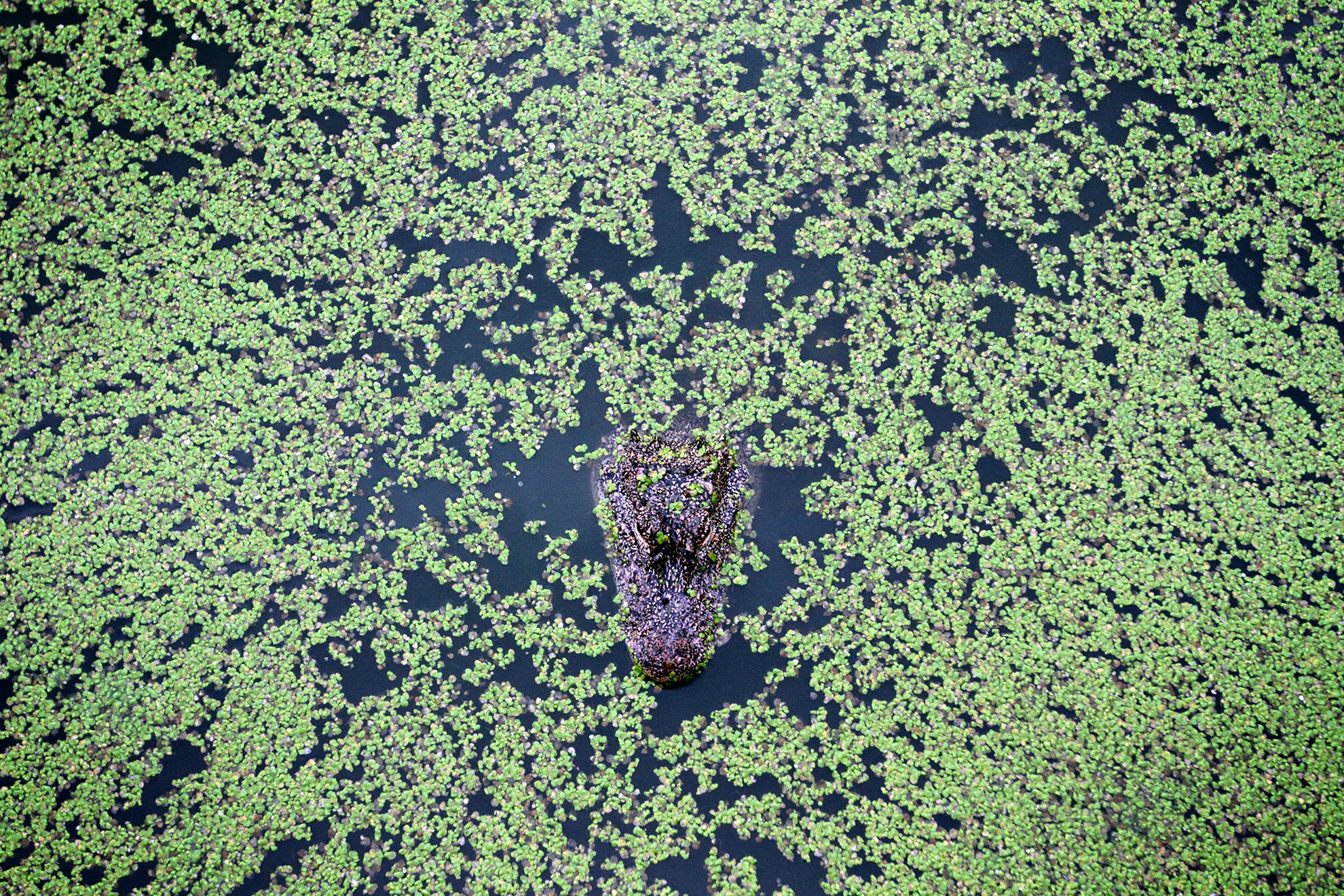

Today, the park welcomes a trickle of visitors who have a chance to walk around many ponds containing thousands of alligators. The alligators are separated into ponds according to size and age, with the youngest being kept away from visitors in small pens behind locked gates. The adults however, are kept by the hundreds in rectangular ponds around which visitors can freely walk, coming nearly within touching distance of the alligators. The largest pond, for the eldest, is an impressive sight; a small lake surrounded by wooded vegetation, the ‘wild enclosure’ replicates the alligators’ natural habitat.

Early one morning, I was invited by the park’s managers to accompany staff whose job it was to collect eggs from the nests of the adult alligators there. We tramped through bushes and undergrowth, following the shore of the lake looking for nests. It didn’t take us long to stumble upon one. Xie Yan from WCS, carefully opened the nest and found a neat pile of around 20 milky-white eggs. Handling them like precious cargo, she and the staff member collected and marked each egg, placing them in a wicker basket to be taken away later to the center’s incubation room where they would stay until hatching.

We continued along the shores of the lake, looking for more nests. As we turned a corner, the staff member excitedly called us over. Next to the shore was a nest and standing guard was a female alligator. I instinctively started to back up. I knew enough about crocodilians to be aware that disturbing a mother protecting her nest was not the best of ideas. Standing only a meter or two away, we watched as the staff member crept up to the nest and looked for eggs. He rummaged through the nest, the alligator’s eyes darting between him and us, but he was unable to find any. We headed back to the main visitors are with a basketful of eggs from the first nest, however, so the morning had been a success. For me, it was a thrilling experience.

As I strolled around the park for a final time, I passed extraneous attractions common to Chinese zoos and aquariums in their attempts to milk a little extra cash out of visitors. There was an area for tourists to have their pictures taken with an alligator. A run-down peacock enclosure stood as a separate exhibit which visitors paid a fee to enter. There was even a supposed ‘reptile zoo,’ which seemed to contain nothing but doves and chickens. Apart from these extra ‘attractions,’ however, the park is obviously on the forefront of saving the Chinese alligator. “More then 1,000 alligators are hatched yearly,” claimed the ARCAR’s brochure. This rapid reproduction is leading to a bulging captive population. Re-introduction into the wild is slow, however, a limited number released from captivity annually.

As the amount of wetlands across China continues to decrease, the question remains: Will it ever be possible to reintroduce so many alligators into the wild when their natural habitats have been all but destroyed?

“Wetlands play a very important role in preserving biodiversity. Almost all the big birds, such as wild goose, ducks, cranes, and migrant birds rely on wetland. That’s why it is so important for animal protection.” urged Xie Yan. “The well-preserved wetland will be the home of the Yangtze alligator in the future.”

For the time being, it appears the captive bred population of Chinese alligators is safe. The same cannot be said, however, for the wild population. Their status remains ‘critcally endangered,’ according to the IUCN’s classification. The slow process of reintroduction means the future of the wild Chinese alligator is still well and truly in the balance.