Desertification in China

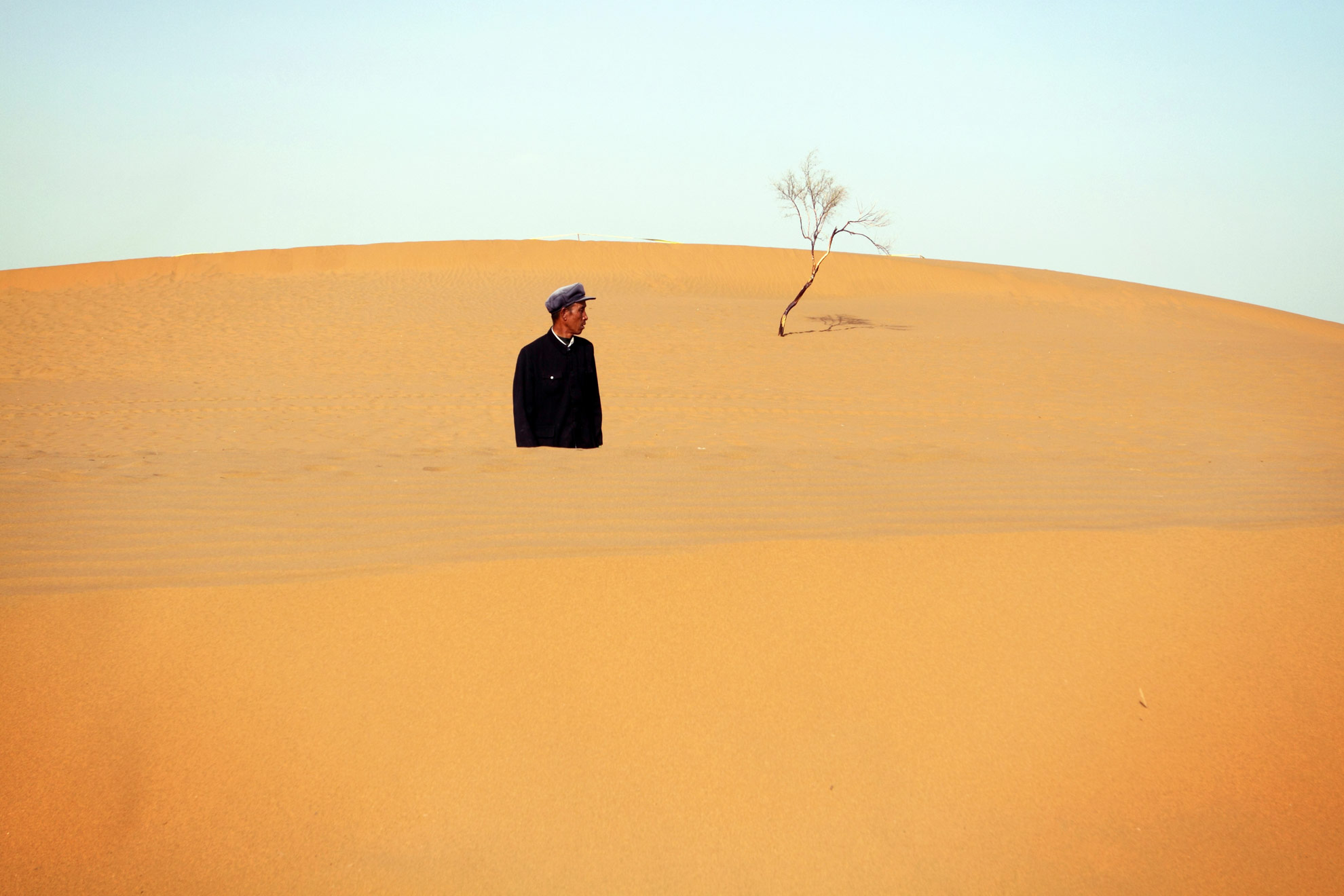

The Black Disaster

“The dryness affects our lives a lot. We call it the ‘black disaster’, which means there is no grass. On the grassland, we are afraid of this disaster”, says Zamusu, a farmer who has lived on the central grasslands of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous region, in Northern China, for the whole of his life. “When I was young, there was much more grass than now”, he continues, in what seems to be a statement echoing across the 70 million acres (28million ha) of the gently undulating grasslands that dominate the Xilamuren steppes north of the region’s capital, Hohhot.

These grasslands are the first stop on my journey across the width of China. Travelling from east to west, in an attempt to document the various facets that surround China’s current fight against desertification. So what is desertification? Desertification is the gradual transformation of arable and/or habitable land into desert, usually caused by local and global climate change and more recently, fuelled by the destructive use of land. So why is it important? Each year, desertification and drought account for US$42 billion loss in food productivity worldwide. In China, approximately 20% of land is now classified as desert or arid, and desertification is affecting the lives of people in China in many ways.

This past week I spent living with a couple who have lived on the Inner Mongolian Grasslands all their lives. Their day-to-day routine is generally quite quiet, following a routine of caring and looking after their animals centered around their modest farmhouse which sits in their 3800 acres of land. Beneath the quiet however lies uncertainty, nervousness and a fear for the future.

These feelings were seeded 20 years ago when local authorities stopped the traditional nomadic practices of farmers moving on the grasslands. The ‘field contract policy’ effectively prohibited people from moving and awarded them with their own plots of land. “No Mongolian people are moving anymore. There is no traditional life anymore”, says Zamasu, “that kind of life stopped from the 1980’s”. Forcing people to graze their animals on the same pieces of land year-in year-out, coupled with pressures on the land from recent economic developments, has led to severe degradation of the grasslands and the increased threat from desertification.

Last year, a new ‘field law’ was introduced to combat over-grazing. The law prohibits farmers from letting their cattle out onto the grasslands to feed and also prevents them from being able to buy new cattle. Even though they risk prosecution, many of the farmers release their cattle just after dark and then retrieve them at sunrise.

It appears that traditional life has long-since disappeared in Inner Mongolia. In an effort to survive, under a system which seems to be strangling them, the future seems decidedly uncertain for the farmers. Meanwhile, the degradation of the grasslands quietly continues around them.

Environmental Refugees

Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region is a small province lying in Loess highlands of north-central China. Dry and desert-like, it is China’s poorest province and is the least visited by outsiders.

I am here this week to visit the isolated town of Hongsibao, which lies 150km south of the province’s capital Yinchuan, completely surrounded by dry and arid land. Ten years ago, this town didn’t exist.

At a cost of more than 2 billion Chinese Renminbi, the town has been constructed, literally on top of the desert. Officially titled the ‘Hongsibao Development Zone Poverty Reduction Project’, some 200,000 people have been relocated from local mountainous areas, suffering as a result of the harsh, dry climes of Ningxia province.

“We’ve already been here three years”, says Mrs Li a young storeowner in the center of town. “We moved from Guyuan in the mountains, in southern Ningxia. Some people left the mountain area but some people didn’t want to move. I think life now is much better than before in the mountains because I only had a field, but now I have a small business to earn some money.”

Even though construction has been taking place for 10 years, the town is still clearly developing and for some, isn’t providing the opportunities promised. “I thought there would be more business here”, says Mr Gao, a taxi driver in Hongsibao who voluntarily moved to the area from neighbouring Shanxi province. “I came here to earn some money but I found that it’s not so good. I want to sell my car and go back home.”

As the wind rattles across the wide boulevards that criss-cross the town, dust and sand is readily picked up from the surrounding deserts and blankets the town during the spring. “In March, the winds start to blow”, sighs Mrs Ma who owns a small Muslim restaurant in the centre of town. “When the wind is blowing, you can’t really see anything. It is the same every year.

Having spoken to many people in the town, it appears that the general feelings towards relocation have been positive. People speak of the improvements in their lives, especially those moved from the poorer mountainous areas. Hongsibao still clearly faces many challenges however, in both it’s development and tackling of it’s harsh and unforgiving location.

“This town isn’t perfect at the moment”, says Mrs Ma, as she turns over another batch of lamb kebabs outside her small restaurant. “Considering the development to now though, after a few years, this town will be very good.”

Yellow Skies

You can smell a sandstorm. As I woke this morning, my throat was drier than normal and the smell of dust and sand had crept into my room whilst I was sleeping. I opened my curtains expecting to see the Yellow River out of my window but all I could see was a haze of yellow light.

Sandstorms have been one of the major problems as a result of desertification in China. As the spring winds blow, dry and degraded topsoil is picked up and thrown into the air to be carried in immense clouds of sand and dust.

Each year, the spring sandstorms that plague northern China, originate here in the northern central desert regions of the country. Moving east, the sandstorms descend on China’s capital Beijing, shrouding it in a surreal yellow light. In recent years, these same sandstorms have been known to be carried on to South Korea, Japan and even as far as the west coast of the United States.

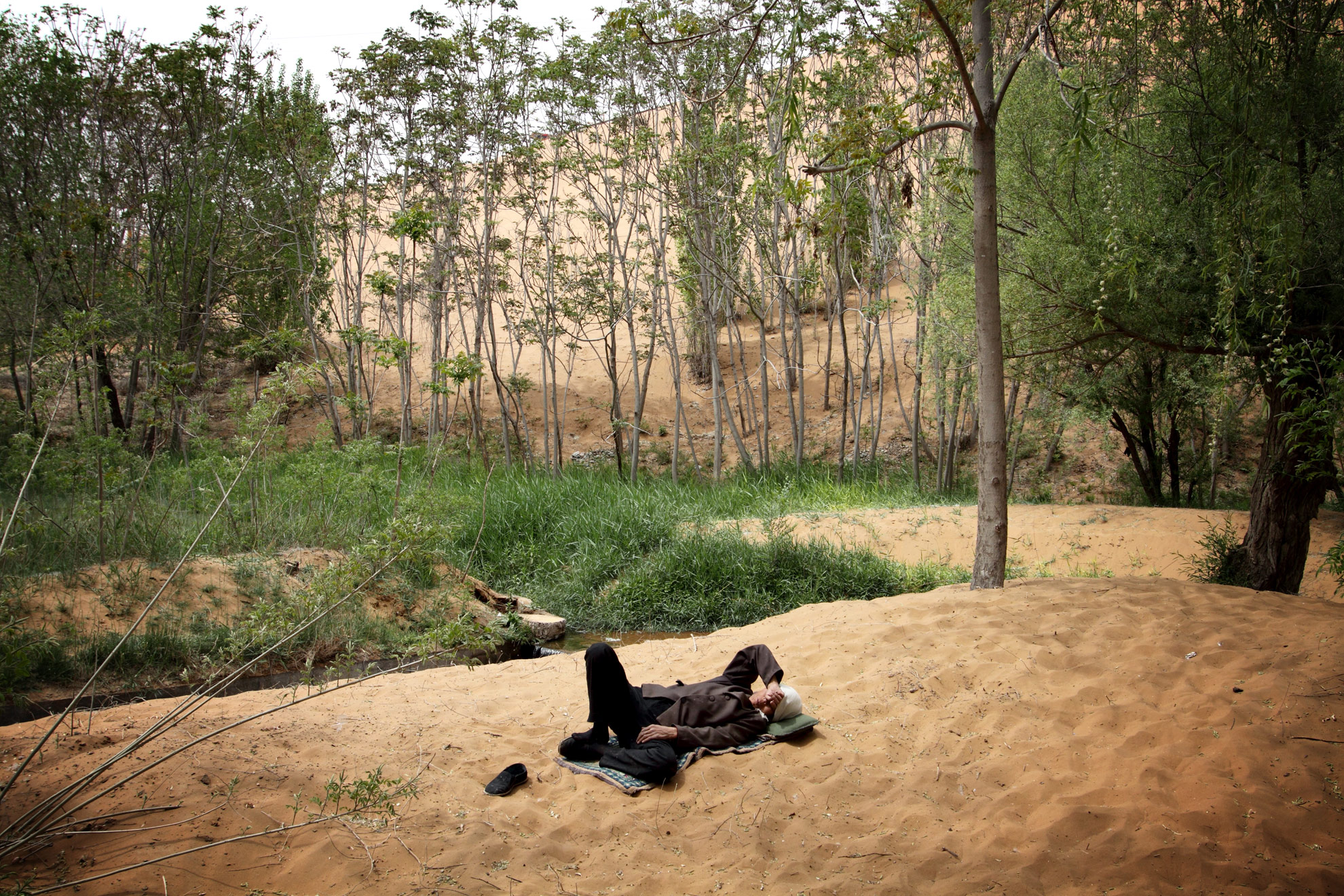

China has taken great efforts in its fight against sandstorms. Attempts have been made to stabilise soils in the west and China is even attempting to build what is known as the ‘Great Green Wall’, a belt of trees some 2800 miles long, being planted in an effort to protect the capital.

During what is meant to be sandstorm season, this is my first experience of a full-blown sandstorm since leaving Beijing three weeks ago. As I journey across the country, I have made a point to ask people about the severity and frequency of sandstorms in recent years. The general opinion is that they are decreasing in frequency as a result of the country’s efforts to fight desertification. Judging by the severity of this storm and its efficiency in bringing life to a standstill, I can only hope this to be true and their opinions aren’t a result of propaganda.

As I continually wipe the dust from my camera equipment, it is hard to imagine how such a powerful force can be tamed. The sand and dust gets everywhere. The sun disappears. I can only move on further, into the yellow cloud that envelops me.